|

'The Kiss' is inspired by

Dantes 'Divine Comedy' and also known as 'Paolo and Francesca' (not to be

mixed up with several horizontal

versions of the same name).

In Canto V of the 'Inferno',

Dante and Virgil meet the illicit love couple Paolo and Francesca in the

Second Circle of Hell, where the carnal sinners are punished. Dante's

narration is based on historical facts that must have deeply impressed him

as a young man: In 1275, Francesca, daughter of Guida Vecchio da Polenta

of Ravenna, was married for political reasons to Giovanni Malatesta, son

and heir of the Lord of Rimini. Giovanni was physically deformed and

Francesca fell in love with his younger brother Paolo, a handsome Captain

of the People in Florence. The love couple was stabbed to death by

Francesca's jealous husband. Francesca was the mother of a nine-year-old

daughter, while Paolo, who was married as well, left two children behind.

This occurred in 1285, when Dante, raised in Florence, was 17 years old.

During the last years of his life in exile, Dante lived at the court of

Francesca's nephew Guido, Lord of Ravenna, so that we may conclude this

human tragedy played more than just a peripheral role in Dante's life.

In the Divina Commedia,

Francesca relates to Dante how both were taken by the reading of

Lancelot's love till Paolo gave his sister-in-law this fatal kiss, not

suspecting they were being observed by Giovanni (or Giancotto), Lord of

Rimini:

|

Noi leggiavamo un giorno

per diletto

di Lancialotto come amor lo strinse;

soli eravamo e sanza alcun sospetto.

Per piu fiate li occhi ci sospinse

quella lettura, e scolorocci il viso;

ma solo un punto fu quel che ci vinse.

Quando leggemmo il disiato riso

esser basciato da cotanto amante,

questi, che mai da me non fia diviso,

la bocca mi bascio tutto tremante.

Galeotto fu 'l libro e chi lo scrisse:

quel giorno piu non vi leggemmo avante." |

One day we reading were

for our delight

Of Launcelot, how Love did him enthral.

Alone we were and without any fear.

Full many a time our eyes together drew

That reading, and drove the colour from our faces;

But one point only was it that o'ercame us.

When as we read of the much-longed-for smile

Being by such a noble lover kissed,

This one, who ne'er from me shall be divided,

Kissed me upon the mouth all palpitating.

Galeotto was the book and he who wrote it.

That day no farther did we read therein." |

|

|

|

|

For this sign of affection, the young lovers were not only

murdered, but eternally damned as well. Their love, intercepted in

its first moment of romantic blossoming was never consumated; the

freshness of their desire was conservated in many works of Art

throughout the centuries.

|

|

|

Felice Giani,

Paolo & Francesca surprised by Gianciotto,

1800-13 c., penna e bistro su carta, Biblioteca Civica, Forlì |

Anselm Feuerbach,

Paolo & Francesca,

1864, Schack-Galerie, Munich |

|

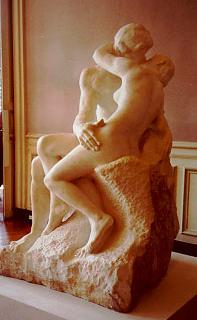

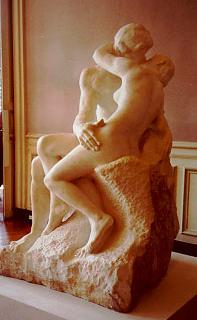

Rodin choose to execute this popular motif

without much reference to the historical pair and the literary

source of the story. Both his preparatory sketches and a small

clay model showing two lovers (around 1880, 13.1 cm high) already

show his characters as nude, like in the final version. This

nudity may seem daring, but for Rodin, it was a necessary quality

to integrate the couple into the scenery of writhing bodies he had

designed. |

|

|

As a reference to Dante's narration, only the book

in Paolo's left hand has remained. The scene, devoid of decoration and

allusion, is concentrated on the performance of the kiss itself. The

bodies are shivering with anticipation and are revelling in their

emotions.

As demonstrated by Michael Klinkenberg, Rodin must have

used the adaption of Dante's Inferno by Rivarol. The linguist

Rivarol had produced no straight translation, but rather had adapted the

poem's idiom and some narrative details in order to transpose and

"elevate" Dante's creation till it met the stylistic criteria of

his own time. In the discussed scene, Rivarol had inserted a description

of the book, sliding from Paolo's hand - a detail not mentioned in Dante's

original text, but explicitly depicted by Rodin. It was also Rivarol who

had induced a positive valuation of the adultry condemned by Dante, by

closing the scene with a sentence completely of his own:

-------------

Initially,

the group, already included in the third maquette of 'The

Gates of Hell', was to take a dominant position on its left door,

building a counter-weight to 'Ugolino

and his Sons' on the right wing. After viewing an early version of

this monumental composition in Rodin's studio in 1885, Mirbeau reported on

a seated Francesca with "her arms around her lover's neck, abandoning

herself to Paolo's kiss and embrace with a movement at once passionate and

chaste." But as observed by Elsen, among others, in Rodin's interpretation of the

subject it rather looks as if Francesca herself has taken the initiative.

Whereas in 'The Minotaur' (1886), a greedy

male brute has forced a resisting virgin onto his furry lap, in 'The Kiss'

it is the woman who intendingly drapes her leg over her partner's limbs.

In the early version Mirbeau had seen, Paolo's right hand is touching

Francesca´s tigh with only three fingertips, the thumb standing off.

Compared to the sensual flow of the female body, Paolo's gestures appear

stiff and reluctant. Already Paul Claudel - who

interpreted the work as a token for his sister's surrender to the woed

sculptor - criticised Paolo´s attitude as that of a man sitting at the

dinner table, the woman being served to him. Initially,

the group, already included in the third maquette of 'The

Gates of Hell', was to take a dominant position on its left door,

building a counter-weight to 'Ugolino

and his Sons' on the right wing. After viewing an early version of

this monumental composition in Rodin's studio in 1885, Mirbeau reported on

a seated Francesca with "her arms around her lover's neck, abandoning

herself to Paolo's kiss and embrace with a movement at once passionate and

chaste." But as observed by Elsen, among others, in Rodin's interpretation of the

subject it rather looks as if Francesca herself has taken the initiative.

Whereas in 'The Minotaur' (1886), a greedy

male brute has forced a resisting virgin onto his furry lap, in 'The Kiss'

it is the woman who intendingly drapes her leg over her partner's limbs.

In the early version Mirbeau had seen, Paolo's right hand is touching

Francesca´s tigh with only three fingertips, the thumb standing off.

Compared to the sensual flow of the female body, Paolo's gestures appear

stiff and reluctant. Already Paul Claudel - who

interpreted the work as a token for his sister's surrender to the woed

sculptor - criticised Paolo´s attitude as that of a man sitting at the

dinner table, the woman being served to him.

By

September 1887, the 'Ugolino' group had been moved to the left wing; 'The Kiss' had been replaced by another representation of the famous

love couple, 'Fugit Amor', now at the

right leaf, showing Paolo and Francesca falling down together, Paolo

desperately clutching to his lover. Maybe the change was made because the

half-life-size 'Kiss' was simply too large, maybe because - due to its affirmative stance introduced by Rivarol -

this tender embrace looked too idyllic against the gloomy background of

the doors. By

September 1887, the 'Ugolino' group had been moved to the left wing; 'The Kiss' had been replaced by another representation of the famous

love couple, 'Fugit Amor', now at the

right leaf, showing Paolo and Francesca falling down together, Paolo

desperately clutching to his lover. Maybe the change was made because the

half-life-size 'Kiss' was simply too large, maybe because - due to its affirmative stance introduced by Rivarol -

this tender embrace looked too idyllic against the gloomy background of

the doors.

In 1887, Rodin executed 'The Kiss' in a small

plaster version (probably) under the title 'The Lovers'. The same year,

this work was shown for the first time in the Gallery Georges Petit

in Paris, then in Brussels. His interpretation of pure pleasure shocked

the public. The incensed critics, who were already excited by his

'Balzac', were urging Rodin to rename his sculpture simply 'The Kiss'.

Rodin himself did not understand much of this turmoil, describing his

composition to Paul Gsell as rather conventional:

"The embrace of The Kiss is undoubtedly very

attractive", he acknowledged. "But I have found nothing in this

group. It is a theme frequently treated in the academic tradition, a

subject complete in itself and artifically isolated from the world

surrounding it; it is a big ornament sculpted according to the usual

formula and which focuses attention on the two personages instead of

opening up wide horizons to daydreams."

1888 Rodin received finally a commission for a marble

version by the Directorate of Fine Arts. 'The Kiss' was enlarged to

more than twice its original size and executed in marble by Rodin's highly

talented praticien Jean Turcan. Turcan's efforts, however, were

interrupted, so that this version could only be presented at the 1898 May Salon

of the Sociéte Nationale des Beaux-Arts.

Amazingly enough, in this version of the group, that by now is recognized

by a worldwide public as a symbol of erotic passion, Paolo is not equipped

for having sex. Only for the so-called "Lewes Kiss", ordered by the private

collector and archeologist Edward Perry Warren, the male genitals were

worked out, as requested by Warren in writing. In June 1900, Rodin's

secretary William Rothenstein noted:

Amazingly enough, in this version of the group, that by now is recognized

by a worldwide public as a symbol of erotic passion, Paolo is not equipped

for having sex. Only for the so-called "Lewes Kiss", ordered by the private

collector and archeologist Edward Perry Warren, the male genitals were

worked out, as requested by Warren in writing. In June 1900, Rodin's

secretary William Rothenstein noted:

Il [Warren] m´écrit de vous prier, comme c´est pour

lui-même qu´il désire 'le baiser' de bien vouloir, dans la réplique,

modeler le sexe de l´homme, comme aurait fait un Grec - il suppose que

dans le groupe du Luxembourg vous avez un peu supprimé ce detail, à

cause de la pudeur muséique.

[Quoted by Anna Tahinci, p. 180-181, FN 354]

The Warren example was executed in Pentelican marble - a

most brittle and demanding material - and shown in the Town Hall of the

City of Lewes, till it provoked the indignation of the local citizenship

and was stored in a barn over decades. Only in the 1970's, the precious

sculpture was rediscovered and transferred to the Tate Gallery in

London.

Also in the year 1900, a further marble example was

ordered by the initiator of the Copenhagen Sculpture Museum, Carl

Jacobsen.

The Barbedienne-LeBlanc Foundry, which in 1898 obtained

a 20-year license to produce an unnumbered mass edition of Rodin´s most

popular sculptures, used a plaster drawn from Turcan´s marble version to

have a reduction made. Of this "third-hand" work (Elsen ), lacking

much of the original detail, 319 examples were sold. Even after Rodin´s

death, the foundry continued to distribute illegal copies, which ended in

a trial and imprisonment for its owners.

BIBLIOGRAPHY (supplied by The

National Gallery of Art, Washington):

Anonymous. "Current

Art." Magazine of Art (1883): 176. Anonymous. "Current

Art." Magazine of Art (1883): 176.

Cartwright, Julia.

"Francesco da Rimini." Magazine of Art (February 1884):

137-139. Cartwright, Julia.

"Francesco da Rimini." Magazine of Art (February 1884):

137-139.

Mirbeau, Octave.

"Chronique Parisienne." La France (18 February 1885). Mirbeau, Octave.

"Chronique Parisienne." La France (18 February 1885).

Bartlett, Truman H.

"Auguste Rodin, Sculptor." Bartlett, Truman H.

"Auguste Rodin, Sculptor."

American Architect and

Building News (19 January-15 June 1889): 200, 223-225, 249. "Le

Baiser dans l'oeuvre de Rodin." La Critique (20 November 1900). American Architect and

Building News (19 January-15 June 1889): 200, 223-225, 249. "Le

Baiser dans l'oeuvre de Rodin." La Critique (20 November 1900).

Lawton, Frederick. The

Life and Work of Auguste Rodin. London, 1906: 62-63, 74, 109-110,

184. Lawton, Frederick. The

Life and Work of Auguste Rodin. London, 1906: 62-63, 74, 109-110,

184.

Grappe, Georges.

Catalogue du Musée Rodin. Paris, 1927: 47. Grappe, Georges.

Catalogue du Musée Rodin. Paris, 1927: 47.

Grappe, Georges.

Catalogue du Musée Rodin. 5th ed. Paris, 1944: 58-59. Grappe, Georges.

Catalogue du Musée Rodin. 5th ed. Paris, 1944: 58-59.

Alley, Ronald. Tate

Gallery Catalogues: The Foreign Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture. London,

1959: 224-226. Alley, Ronald. Tate

Gallery Catalogues: The Foreign Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture. London,

1959: 224-226.

Elsen, Albert E. Rodin.

New York, 1963: 62-63, 102-103, 134, 191, 199, 209. Elsen, Albert E. Rodin.

New York, 1963: 62-63, 102-103, 134, 191, 199, 209.

Summary Catalogue of

European Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington,

1965: 168. Descharnes, Robert, and Jean-François Chabrun. Auguste Rodin.

Lausanne, 1967: 131-135. Summary Catalogue of

European Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington,

1965: 168. Descharnes, Robert, and Jean-François Chabrun. Auguste Rodin.

Lausanne, 1967: 131-135.

European Paintings and

Sculpture, Illustrations. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1968: 148,

repro. European Paintings and

Sculpture, Illustrations. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1968: 148,

repro.

Wasserman, Jeanne L.,

ed. Metamorphoses in Nineteenth-Century Sculpture. Exh. cat. Fogg Art

Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1975: 168-176. Wasserman, Jeanne L.,

ed. Metamorphoses in Nineteenth-Century Sculpture. Exh. cat. Fogg Art

Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1975: 168-176.

de Caso, Jacques, and

Patricia B. Sanders. Rodin's Sculpture: A Critical Study of the Spreckels

Collection. San Francisco, 1977: 148-153. de Caso, Jacques, and

Patricia B. Sanders. Rodin's Sculpture: A Critical Study of the Spreckels

Collection. San Francisco, 1977: 148-153.

Rosenfeld, Daniel.

"Rodin's Carved Sculpture." In Rodin Rediscovered. Exh. cat.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1981: 85-87. Rosenfeld, Daniel.

"Rodin's Carved Sculpture." In Rodin Rediscovered. Exh. cat.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1981: 85-87.

Elsen, Albert E. The

Gates of Hell by Auguste Rodin. Stanford, California, 1985: 78-81. Elsen, Albert E. The

Gates of Hell by Auguste Rodin. Stanford, California, 1985: 78-81.

Barbier, Nicolle.

Marbres de Rodin: collection du musée. Paris, 1987: 184-187. Barbier, Nicolle.

Marbres de Rodin: collection du musée. Paris, 1987: 184-187.

Grunfeld, Frederic V.

Rodin: A Biography. New York, 1987: 187-190. Grunfeld, Frederic V.

Rodin: A Biography. New York, 1987: 187-190.

Beausire, Alain. Quand

Rodin Exposait. Paris, 1988: 95, 96, 126, 211, 277, 327, 349, 351,

367. Beausire, Alain. Quand

Rodin Exposait. Paris, 1988: 95, 96, 126, 211, 277, 327, 349, 351,

367.

Fonsmark, Anne-Birgitte.

Rodin: La collection du Brasseur Carl Jacobsen à la Glyptothèque.

Copenhagen, 1988: 106-108. Fonsmark, Anne-Birgitte.

Rodin: La collection du Brasseur Carl Jacobsen à la Glyptothèque.

Copenhagen, 1988: 106-108.

Barbier, Nicolle. Rodin

sculpteur: Oeuvres méconnues. Exh. cat. Musée Rodin, Paris, 1992:

187-190. Barbier, Nicolle. Rodin

sculpteur: Oeuvres méconnues. Exh. cat. Musée Rodin, Paris, 1992:

187-190.

Rosenfeld, Daniel G.

Auguste Rodin's Carved Sculpture. Ph.D. diss., Stanford University, 1993:

529-540. Sculpture: An Illustrated Catalogue. Rosenfeld, Daniel G.

Auguste Rodin's Carved Sculpture. Ph.D. diss., Stanford University, 1993:

529-540. Sculpture: An Illustrated Catalogue.

National Gallery of Art,

Washington, 1994: 204, repro. Le Normand-Romain, Antoinette. National Gallery of Art,

Washington, 1994: 204, repro. Le Normand-Romain, Antoinette.

Le Baiser de Rodin. Exh. cat. Musée Rodin, Paris, 1995: 244-319.

Kausch, Michael. Auguste

Rodin: Eros und Leidenschaft. Exh. cat. Harrach Palace, Kunsthistorisches

Museum, Vienna, 1996: 146-147. Kausch, Michael. Auguste

Rodin: Eros und Leidenschaft. Exh. cat. Harrach Palace, Kunsthistorisches

Museum, Vienna, 1996: 146-147.

Butler, Ruth, and

Suzanne Glover Lindsay, with Alison Luchs, Douglas Lewis, Cynthia J.

Mills, and Jeffrey Weidman. European Sculpture of the Nineteenth Century.

The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue.

Washington, D.C., 2000: 326-330, color repro. Butler, Ruth, and

Suzanne Glover Lindsay, with Alison Luchs, Douglas Lewis, Cynthia J.

Mills, and Jeffrey Weidman. European Sculpture of the Nineteenth Century.

The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue.

Washington, D.C., 2000: 326-330, color repro.

|

Initially,

the group, already included in the third maquette of

Initially,

the group, already included in the third maquette of  By

September 1887, the 'Ugolino' group had been moved to the left wing; 'The Kiss' had been replaced by another representation of the famous

love couple,

By

September 1887, the 'Ugolino' group had been moved to the left wing; 'The Kiss' had been replaced by another representation of the famous

love couple,  Amazingly enough, in this version of the group, that by now is recognized

by a worldwide public as a symbol of erotic passion, Paolo is not equipped

for having sex. Only for the so-called "Lewes Kiss", ordered by the private

collector and archeologist Edward Perry Warren, the male genitals were

worked out, as requested by Warren in writing. In June 1900, Rodin's

secretary William Rothenstein noted:

Amazingly enough, in this version of the group, that by now is recognized

by a worldwide public as a symbol of erotic passion, Paolo is not equipped

for having sex. Only for the so-called "Lewes Kiss", ordered by the private

collector and archeologist Edward Perry Warren, the male genitals were

worked out, as requested by Warren in writing. In June 1900, Rodin's

secretary William Rothenstein noted: