|

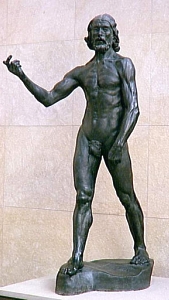

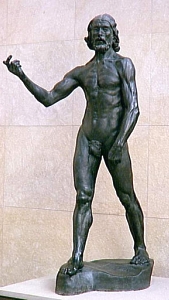

In 1877, Rodin began with first studies on a monumental sculpture of 'St.

John the Baptist Preaching'. Responding to the critics who had accused him

to have used casts after life for 'The

Age of Bronze' he modeled his figure larger than life-size.

In 1877, Rodin began with first studies on a monumental sculpture of 'St.

John the Baptist Preaching'. Responding to the critics who had accused him

to have used casts after life for 'The

Age of Bronze' he modeled his figure larger than life-size.

Rodin's interpretation of St. John the Baptist is that of a man preaching

while walking. Although both feet are fixed on the ground with the whole

sole - like in an Egyptian sculpture - the work procures the dynamic

impression of a man that resolutely goes his way. To his friend Paul

Gsell, Rodin later explained how he visualised two phases of a stride

simultaneously in order to suggest movement:

"Now, the illusion of life is obtained in our art by

good modelling and by movement.(..)

"Note, first, that movement is the transition from one attitude to

another. (...)

"You have certainly read in Ovid how Daphne was transformed into a

bay-tree and Procne into a swallow. (...) In each of them one still sees

the woman which will cease to be and the tree or birds which she will

become.

"It is, in short, a metamorphosis of this kind that the painter or

the sculptor effects in giving movement to his personages. He represents

the transition from one pose to another - he indicates how insensibly the

first glides into the second. In his work we still see a part of what was

and we discover a part of what is to be. (...)

"Now, for example, while my Saint John is represented with both

feet on the ground, it is probable that an instantaneous photograph from a

model making the same movement would show the back feet already raised and

carried forward to the other. Or else, on the contrary, the front feet

would not yet be on the ground if the back leg occupied in the photography

the same positions as in my statue."Now it is exactly for that reason

that this model photographed would present the odd appearance of a man

suddenly stricken with paralysis and petrified in his pose (..)

"If, in fact, in instantaneous photographs, the figures, though taken

while moving, seem duddenly fixed in mid-air, it is because, all parts of

the body being reproduced exactly at the same twentieth or fortieth of a

seconds, there is no progressive development of movement as there is in

art. (...)

"It is the artist who is truthful and it is photography which lies,

for in reality time does not stop, and if the artist succeeds in producing

the impression of a movement which takes several moments for

accomplishment, his work is certainly much less conventional than the

scientific image, where time is abruptly suspended.

Rodin certainly was familiar with historical examples of statues of St.

John, like 'St. John the Baptist' by Giovanni Francesco Rustici

(Baptistery of Florence). Although the poses are very similar, Rodin shows his Baptist without

the traditional attributes of St. John - the sheepskin-coat and the cross.

His striding saint is nude, unidealized and crudely modeled. As could be

expected, the work met severe critique; most recipients found it improper,

even ugly and shocking.

Rodin certainly was familiar with historical examples of statues of St.

John, like 'St. John the Baptist' by Giovanni Francesco Rustici

(Baptistery of Florence). Although the poses are very similar, Rodin shows his Baptist without

the traditional attributes of St. John - the sheepskin-coat and the cross.

His striding saint is nude, unidealized and crudely modeled. As could be

expected, the work met severe critique; most recipients found it improper,

even ugly and shocking.

De Caso and Sanders describe Rodin’s 'St. John' as follows:

"The exaggeration of certain anatomical parts, like the

bulging muscles of back and arms and the ribs pushing through the chest,

anticipate sculptures like The Thinker. However, a difference in

proportions is apparent, for the St. John is slight and bony. The contrast

between muscularity and wiry build suggests the ascetic habits of the

desert dweller and the strength of his convictions. With his unusual

figure type and with the unique method for representing movement, Rodin

was able to create a sculpture with a forceful presence unlike anything

his contemporaries had ever seen."

Like for 'The Age of

Bronze', it was again the personality of the model that inspired Rodin

for 'The Baptist'. He once told Dujardin-Beaumetz:

"One morning, someone knocked at the studio door. In

came an Italian, with one of his compatriots who had already posed for me.

He was a peasant from Abruzzi, arrived the night before from his

birthplace, and he had come to me to offer himself as a model. Seeing him,

I was seized with admiration: that rough, hairy man, expressing in his

bearing and physical strength all the violence, but also all the mystical

character of his race. I thought immediately of a St. John the Baptist;

that is, a man of nature, a visionary, a believer, a forerunner come to

announce one greater than himself."

There has been some controversy if it had been César

Pignatelli or rather his countryman Danielli who posed for the work.

Georges Grappe claimed that Danielli had been the model at least for the

head, hereby contradicting a statement by Truman Bartlett. A photo showing

Rodin's model Pugnatelli in the pose of 'The Baptist' seems to prove the

latter has posed at least for the body ; as for the head, even Grappe had

to admit there is only little resemblance between the 'Bust of Danielli'

and the face of 'St John'.

The

sculpture 'The Walking Man' is a version of 'St. John' without head and

arms, focused on the illustration of movement. During Rodin's lifetime,

'The Walking Man' was considered to be a preliminary study for the

complete 'Baptist', and mentioned in exhibition catalogues as such. Judith

Cladel, however, later recalled that Rodin created the 'Walking Man' only

after 1900, employing fragments from previous versions, deliberately

producing a partial figure. The

sculpture 'The Walking Man' is a version of 'St. John' without head and

arms, focused on the illustration of movement. During Rodin's lifetime,

'The Walking Man' was considered to be a preliminary study for the

complete 'Baptist', and mentioned in exhibition catalogues as such. Judith

Cladel, however, later recalled that Rodin created the 'Walking Man' only

after 1900, employing fragments from previous versions, deliberately

producing a partial figure.

Albert Elsen and Henry Moore even suggested 'The Walking

Man' was made on purpose to look like an antiquarian sculpture rooted in

Roman and Greek art, without referral to the live model. Even if

Elsen and Moore were wrong, I determined a striking resemblance to the

sculpture 'Headless Hercules', which was placed in the garden of

Rodin's villa in Meudon ('Headless Hercules', Roman copy after a 4th c. BC

Greek original marble, 183 x 103 x 55 cm, MuRo Co.1107). Even the

different ways the arms have been broken off - leaving a stump at the

dexter side, while at the sinister side, the complete shoulder has been

truncated - is nearly identical in both cases. Rodin considered this

antique torso as the "jewel" of his collection, and once

commented:

"This Hercules, so proudly arched, stands there in the

most unaffected manner. He has been seized at a moment when nobody is

looking at him. Every single muscle is vibrating with the desire to

exercise, but no part of his being displays itself for admiration. It is

in this way too that antique art stands out so sharply from academic art

which claims, illegitimately, to be its descendant."

The headless 'st John' was exhibited for the first time

in Rodin's Pavillon at the Place d'Alma on a high column in 1900.

In 1905, the sculpture was enlarged to over-life size, the right shoulder

being bent slightly forward to amplify the suggestion of movement; only

from that time on, it became known as 'The Walking Man'. The

enlarged bronze version was exhibited for the first time in Strasbourg in

1907, and in the Paris Salon. One bronze cast was donated by

admirers to be placed at the Palazzo Farnese in Rome. Rodin, eager

to see his sculpture combined with the architecture created by

Michelangelo, travelled to Italy in January 1912 together with the

Duchesse de Choiseul and inspected the future site. After the

installation, the cast only stayed there till 1923 and was then returned

to Lyon, France, because it displeased the French Ambassor in Rome.

By now, there are several monumental casts in Museums worldwide.

BIBLIOGRAPHY (supplied by The

National Gallery of Art, Washington):

Grappe, Georges. Catalogue du Musée Rodin. Paris, 1927: 50.

Grappe, Georges. Catalogue du Musée Rodin. Paris, 1927: 50.

Cladel, Judith. Rodin: Sa vie glorieuse, sa vie inconnue. Paris, 1936:

146.

Cladel, Judith. Rodin: Sa vie glorieuse, sa vie inconnue. Paris, 1936:

146.

Grappe, Georges. Catalogue du Musée Rodin. 5th ed. Paris, 1944: 64.

Grappe, Georges. Catalogue du Musée Rodin. 5th ed. Paris, 1944: 64.

Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of

Art, Washington, 1965: 169, as Study for "St. John the Baptist,"

Gates of Hell.

Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of

Art, Washington, 1965: 169, as Study for "St. John the Baptist,"

Gates of Hell.

Descharnes, Robert, and Jean-François Chabrun. Auguste Rodin. Lausanne,

1967: 85, 241.

Descharnes, Robert, and Jean-François Chabrun. Auguste Rodin. Lausanne,

1967: 85, 241.

European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. National Gallery of Art,

Washington, 1968: 149, repro., as Study for "St. John the

Baptist," Gates of Hell.

European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. National Gallery of Art,

Washington, 1968: 149, repro., as Study for "St. John the

Baptist," Gates of Hell.

Tancock, John. The Sculpture of Auguste Rodin. Philadelphia, 1976:

205-209.

Tancock, John. The Sculpture of Auguste Rodin. Philadelphia, 1976:

205-209.

de Caso, Jacques, and Patricia B. Sanders. Rodin's Sculpture: A Critical

Study of the Spreckels Collection. San Francisco, 1977: 85-87.

de Caso, Jacques, and Patricia B. Sanders. Rodin's Sculpture: A Critical

Study of the Spreckels Collection. San Francisco, 1977: 85-87.

Elsen, Albert E. "When the Sculptures Were White: Rodin's Work in

Plaster." In Rodin Rediscovered. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art,

Washington, D.C., 1981: 130.

Elsen, Albert E. "When the Sculptures Were White: Rodin's Work in

Plaster." In Rodin Rediscovered. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art,

Washington, D.C., 1981: 130.

Vilain, Jacques. Claude Monet-Auguste Rodin: Centennaire de l'exposition

de 1889. Exh. cat. Musée Rodin, Paris, 1989: 189.

Vilain, Jacques. Claude Monet-Auguste Rodin: Centennaire de l'exposition

de 1889. Exh. cat. Musée Rodin, Paris, 1989: 189.

Rosenfeld, Daniel G. Auguste Rodin's Carved Sculpture. Ph.D. diss.,

Stanford University, 1993: 413-417.

Rosenfeld, Daniel G. Auguste Rodin's Carved Sculpture. Ph.D. diss.,

Stanford University, 1993: 413-417.

|

The

sculpture 'The Walking Man' is a version of 'St. John' without head and

arms, focused on the illustration of movement. During Rodin's lifetime,

'The Walking Man' was considered to be a preliminary study for the

complete 'Baptist', and mentioned in exhibition catalogues as such. Judith

Cladel, however, later recalled that Rodin created the 'Walking Man' only

after 1900, employing fragments from previous versions, deliberately

producing a partial figure.

The

sculpture 'The Walking Man' is a version of 'St. John' without head and

arms, focused on the illustration of movement. During Rodin's lifetime,

'The Walking Man' was considered to be a preliminary study for the

complete 'Baptist', and mentioned in exhibition catalogues as such. Judith

Cladel, however, later recalled that Rodin created the 'Walking Man' only

after 1900, employing fragments from previous versions, deliberately

producing a partial figure.